Deceptive Engineering

Signs Your Software Engineering Team is Lying to You and How to Mitigate It

As a senior technical leader, you have to get used to being deceived. It isn’t usually nefarious; it's just a mechanism that has been passed down from generation to generation of software engineers to enable them to control what is, and more importantly, what isn’t done. And as bright software engineers, they are really, really good at it.

Why do they do this? There are many reasons why they may actively try to deceive you. They may think the requirement, project, product, or service effort is stupid, wrongheaded, and misguided, and that they know better than the company. They may receive a directive on how to accomplish something, but they don’t like the specificity of the “how,” whether it involves a specific tool, an open-source project, or a component. The engineer(s) might just want to work on something else, and this is getting in the way of them working on that far more desirable, in their minds, product or project. However, my personal favorite is that they become so entrenched in their ways that, regardless of what you, product management, or even their peers on other products might think, they believe they know best how and what to accomplish.

Let me give you some examples of what I’ll call Deceptive Engineering.

I’ll start with a classic, “I have concerns.” My blood almost, but not quite, boils when an engineer or engineering director tells me they have concerns. If any of my engineers wants me to instantly get angry and reach for the Clonidine, it is telling me they have concerns. Why? Because I know after 31 years in this industry that they don’t have concerns, they just don’t want to do it. I don’t even care why they don’t want to do it; they really don’t want to. Usually, after telling you they have concerns, they will rattle off a list of things they have concerns about. You might think they are being deep thinkers or that they have truly considered the problem, but no, they are just listing things off that they hope might undermine what is being presented as work to them, or it will be slowed down while these concerns are investigated.

Fun fact, IBM once had an entire system for “Concerns” called the Nonconcur system. Basically, anyone could raise a concern, and the entire effort had to be paused while that concern was evaluated and mitigated. It was paralyzing to the company.

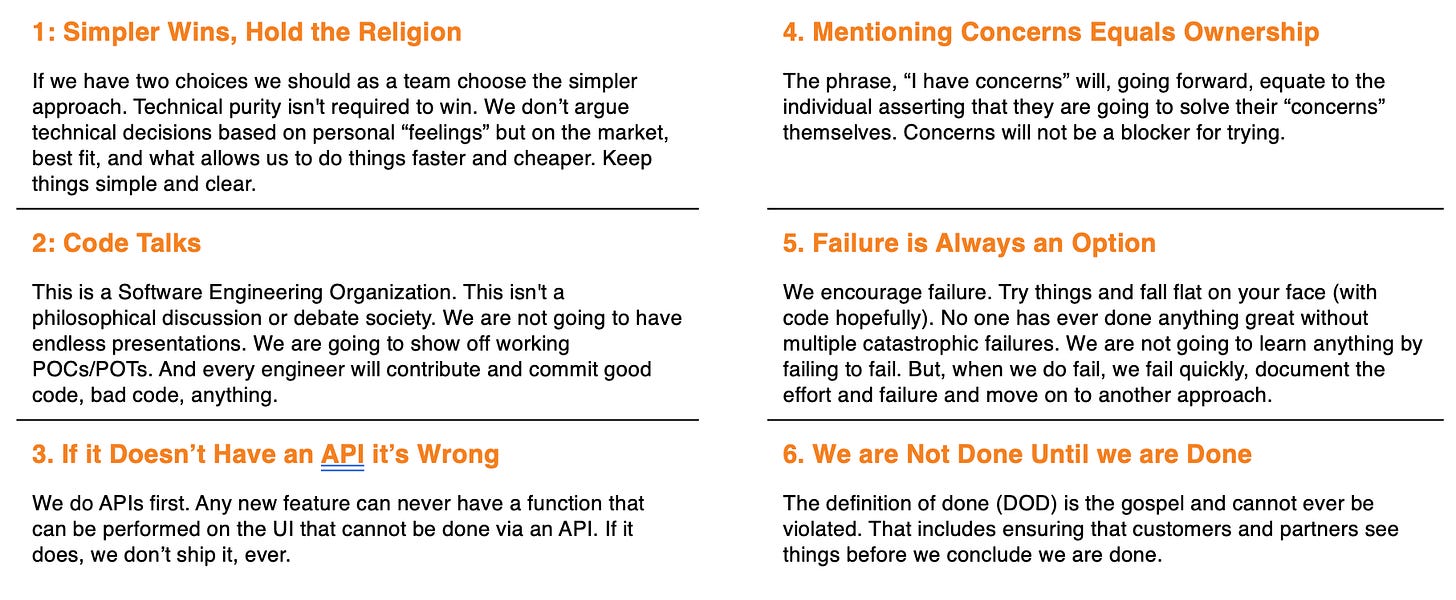

So, how do you handle “Concern” based Deceptive Engineering? It is actually pretty easy once you recognize the characteristics. You simply tell the engineer or engineering leader, “You have concerns, that’s great, congratulations, you now own creating a solution for all of them, I look forward to weekly updates on your progress.” Do that two or three times with your organization, and you will never hear the word “concerns” again.

Security Reviews, this is a somewhat newer one, but it has gained enormously in popularity. I once, without me knowing it was happening, had a team with a successful shipping product that was going to be integrated with a new product, attempt to out-and-out sabotage the proposed integration by using the tool of Security Reviews. How? The existing successful product engineering team went out and spent two weeks devising a brand new Security Review process that, no lie, required the other, new product team to write a 40-page document. Then they conducted a day-long review of the document. And since the new product team was in a distant time zone, the shipping product team scheduled the day-long review at a time that was the middle of the night for the new product engineering team. I mean, I give them an “A” for creativity in shutting down work.

The Deceptive Engineering via Security Reviews is highly effective because security has become a boogeyman in software engineering. It is so very easy for software engineers to say they discovered a security issue or flaw, and so hard for senior leaders to validate them. And let’s be completely honest, no piece of software is ever perfectly free of security flaws. When you have forty blessed pages to pick and choose from (in the example), you are going to find something. In my above example, the security review, though it really found nothing wrong that mattered, was reported up to my boss, along with those forty pages of meaningless material that he couldn’t understand anyway, and the effort was delayed by TWO YEARS over my strenuous objection. When we finally returned to the integration project, it turned out that there was nothing wrong with it to begin with. Shocker!

Lesson learned: Do not let your product engineering teams conduct security reviews. Have a separate team or security leader who has no axe to grind and whom you trust, handle security reviews. Whenever a security problem is identified by one of your engineers, it must be referred to the security team for evaluation. Nothing can stop until that evaluation is complete; coding must continue. I have even implemented a checksum such that if an engineer raises more than five security issues in a year, all of which are determined to be unfounded and frivolous, it will be grounds for being placed on a Performance Improvement Plan (PIP).

As an aside, I recently saw an engineer in a chat raise both concerns and state in the same paragraph that a specific programming language was “known to be insecure.” That's trying really hard to stop or delay something. It’s impressive.

Sizing, are you kidding me? Really, it will take that long to do this proposed component, project, or effort. Engineers have been using Deceptive Engineering via sizing since the ENIAC. They know how long it will really take, but they report something much longer to discourage whatever it is. And it works. How would a project manager or business owner know how long it will take to code something? They aren’t engineers. They are trusting the engineer or the engineering team leader as the expert.

Engineers have even created a whole system within the Agile development methodology (capital A) where they don’t provide time estimates. They have, wait for it, story-points. What is a story-point? That’s the genius of it; it is whatever they want it to be. Story-points even inflate in an engineering organization over time. It is like the engineers have this built-in way to conflate and confuse the business. And all they say over and over again is, “We are just following the Agile Process.”

As the CTO or senior technical executive, how do you stop this “sizing” fraud? I use three methods. The first is to have sizing reviews. All major sizings in my organization are reviewed by another engineer or architect who is from another team and/or product. I don’t expect the reviewing engineer to actually do a new sizing, they just report back if the sizing is reasonable or not. Second, we never expose story-points to the business. If the engineering team is using virtual currency like story-points for measuring work, that’s fine. But we report to the business, dates and effort in person months. Lastly, and I know this is a hard thing to do for a senior executive, I stay current in technology and I can still code. If I see a sizing and it seems off to me, I try to do it myself. Not all of it, just a small segment to get a feel for how hard it really is. Woe be unto the engineer, and colluding review engineer, that tries to slip something past me.

Gobbledygook. In Inside Star Trek: The Real Story, authors Herb Solow and Robert Justman tell a story of how they once when horribly late in delivering the next episode of Star Trek to the network, NBC, used Gobbledygook to provide an excuse. They told an NBC executive who was smart but not well-versed in the making of the films, that they were late because the sprocket holes and the associated machine were broken. The episode was done, and they were just waiting for the machine to be repaired. Now, if you know anything about the making of television and film, Solow and Justman just changed motion-picture technology in the lie they told to the executive. They used their knowledge of technology and some creativity to their advantage.

Software engineers do the same thing. They use their expertise to deceive product managers, engineering leaders, and the business. And boy, are they creative and good at it. They will tell some whoppers like, “Oh, we can’t use open source here because the project you want us to use is written in a programming language that can’t run on our servers.” Or “My repository server is down, can’t get this to you until IT fixes it.”

The easiest way to combat Gobbledygook is knowledge. To be a successful senior technical executive, you have to know your products and their code, know the technical trends, and understand how your pipelines and infrastructure can impact your current efforts. It is hard, for sure. But no one has ever said this industry is for the weak.

Training, seriously, are you kidding me? I was once given a new engineering team from a recent acquisition that needed to create a client-side integration with our existing products. The five senior engineers and architects from this new team met with me in a conference room where they told me, to my face, that they needed the company to give them three months of training because they, some really good and talented Java programmers, did not know and understand JavaScript. Okay, I’ll admit it; I couldn't help but start laughing. For those of you who are not very technical, this is hugely amusing because JavaScript was derived from Java by Brendan Eich over a weekend as a hack.

Engineers will tell you they can’t do something because they don’t know how, that they are experts in another programming language and don’t know X, Y, or Z. It’s just not true. Sure, taking a Java programmer and telling them something has to be implemented in, for example, the Rust programming language, is going to take longer while they get up to speed. But if an engineer tells you they can’t do something in another programming language or with another technology and they require some kind of formal training to do so, you should seriously consider whether they are really an engineer.

This one is the easiest to manage, though it does require you, as a senior leader, to be a bit harsh. Mock them. Publicly. It works, and though it is a bit crass to do it, an engineer who can’t learn and grow probably should not be working for you.

There are more, so many more ways in which Deceptive Engineering manifests. I had an engineer once argue with a lawyer over his legal interpretation of a license so that the engineer could get out of using a specific open-source repository for the basis of a project. All because he wanted to write it himself. Hey, they are certainly creative.

Deceptive Engineering, at its core, is a culture problem. And it will always be in your engineering organization, lurking beneath the surface. However, if you can establish a culture that despises its tendencies and calls them out, even before they manifest, you can keep them at bay and avoid the stories above.